Heat exchangers are widely used in the power generation industries. Particularly, the cross-flow type of heat exchangers are a commonplace. Operating heat exchangers at higher flow rates enhance the heat transfer, due to increased flow turbulence; however, the higher flow rates may lead to flow-induced vibrations. Flow induced vibration in heat exchanger tube bundles has been extensively studied over the last few decades, particularly to better understand the fluidelastic vibration. The failures (Fig.1) due to the fluidelastic instability occur suddenly, which can pose serious risk to the plant operations. In this work, we perform unsteady Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (URANS) as well as large eddy simulations (LES) to elucidate the mechanism of the onset of fluidelastic instability.

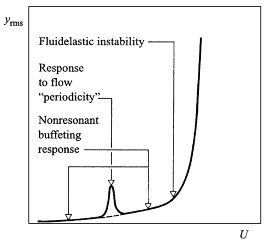

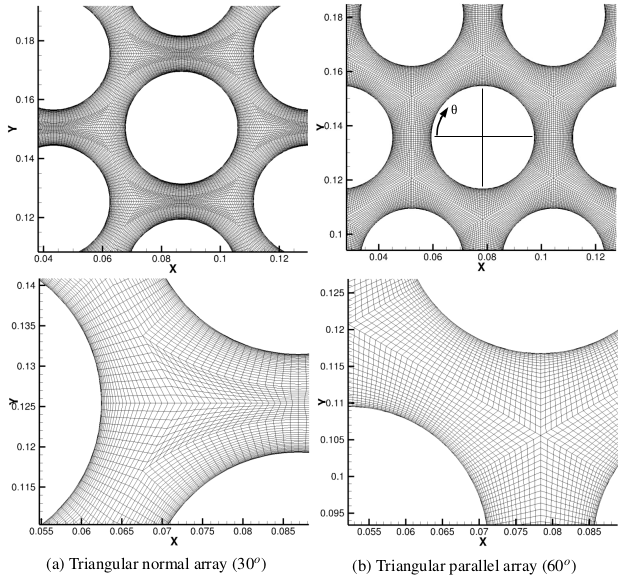

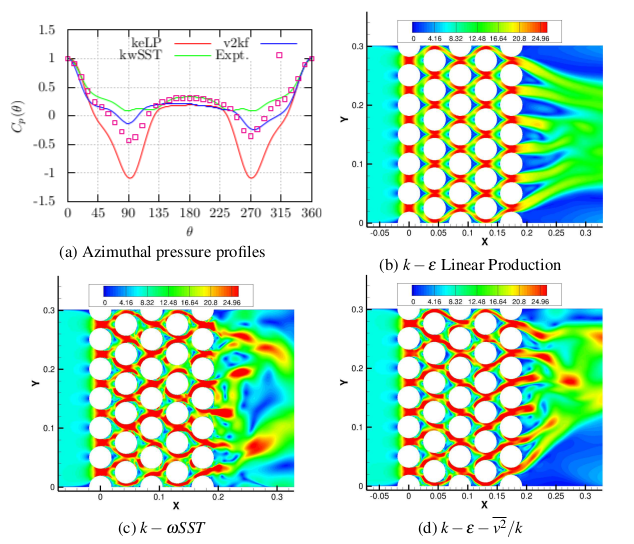

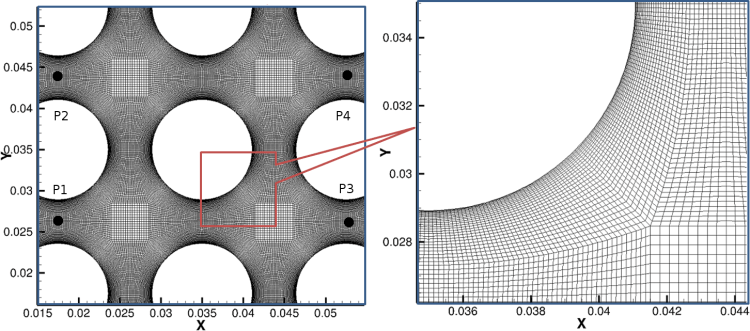

Fluidelastic instability is a self excitation phenomenon, similar to the high-speed aeroelastic flutter or low speed galloping instability, where an initial movement of structure leads to higher forces, and consequently very large magnitude vibration. At first, we explored the instability by performing unsteady Reynolds averaged Navier-Stokes (URANS) CFD simulations, by considering several turbulence models, namely k-e LP, k-w SST, and k-e-v2-f. Keeping in mind the unsteady nature of fluidelastic instability, we verified the different RANS models for the prediction of the onset of instability. Figure 2 displays the computational mesh and the azimuthal pressure and velocity flow fields for triangular parallel arrangement of tubes, indicating, to some degree, better prediction with k-e-v2-f turbulence model. Although the URANS predict the critical value of the flow velocity for the onset of fluidelastic instability, the detailed dynamics, in terms of the structural frequency and damping, between the cylinder and surrounding flow fields is not well captured.

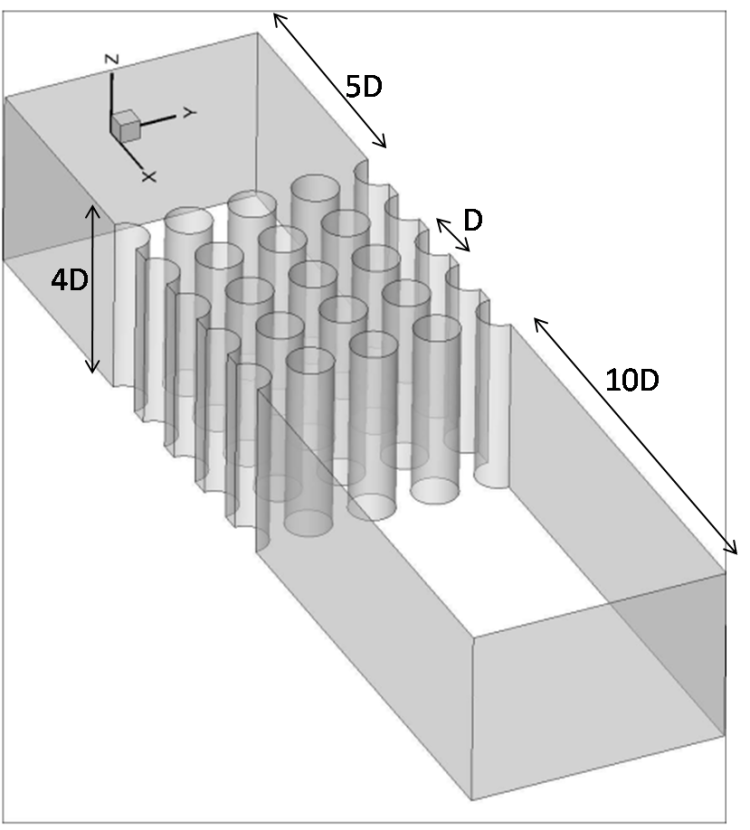

Large eddy simulation (LES), on the other hand, suitably captures the large scale unsteadiness in the turbulence, including the multiphysics dynamics. The present CFD efforts, to elucidate the fluidelastic instability, were accompanied by experiments at the French Alternative Energies and Atomic Energy Commission (CEA). The LES were patterned after the experimental setup, which comprised a small group of cylinder in square normal arrangement subjected to water cross flow, where the central cylinder was flexibly mounted to investigate the instability. The LES domain and mesh are shown in Fig.3.

The high-fidelity LES are performed by using Smagorinsky-Lilly subgrid scale model. Although the flow solver has more popular dynamic Smagorinsky and wall-adapting local eddy-viscosity (WALE) models, the original model with appropriate value of Smagorinsky constant was used considering the moving mesh due to fluid-structure interaction. Briefly, the model uses Boussinesq hypothesis to account the effect of subgrid turbulence scales on the large eddies. The eddy viscosity is assumed to be proportional to the local strain-rate tensor and grid size, where the constant of proportionality is based on Kolmogorov’s hypothesis, which states that the production and dissipation of turbulence equals in the inertial range, leading to the value of 0.18 for the constant in isotropic flows. However, for non-isotropic flow the value may vary, for example, for the plane channel flow it is approximately 0.065.

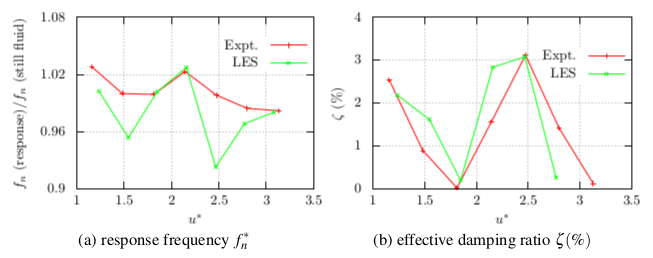

The LES results are shown in Fig.4 in terms of cylinder response frequency and damping of vibration for increasing velocity upto the onset of instability, exhibiting good agreement with the experimental results. Notably, LES captures the sinusoidal variations in the cylinder response dynamics for increasing velocity.

To examine the nature of interactions between the flexible cylinder and interstitial velocity fields, the LES flow fields (the velocity and wall pressure) along with the cylinder motion were analyzed for increasing velocity (see Fig.5). It becomes apparent that the initial small oscillations of the cylinder perturb the surrounding flow field, which in turn affects the oscillations. For different flow velocities, the synchronization either promotes or hinders the cylinder oscillations, leading to the sinusoidal response (of Fig. 4) for increasing velocity. Thus, at high velocity, where the absolute forces are higher, the cylinder can exhibit vigorous oscillations (when synchronized with the surrounding flow fields), resulting in the onset of instability. In the present work, LES has been instrumental in uncovering the physics of interaction underlying the fluidelastic instability.